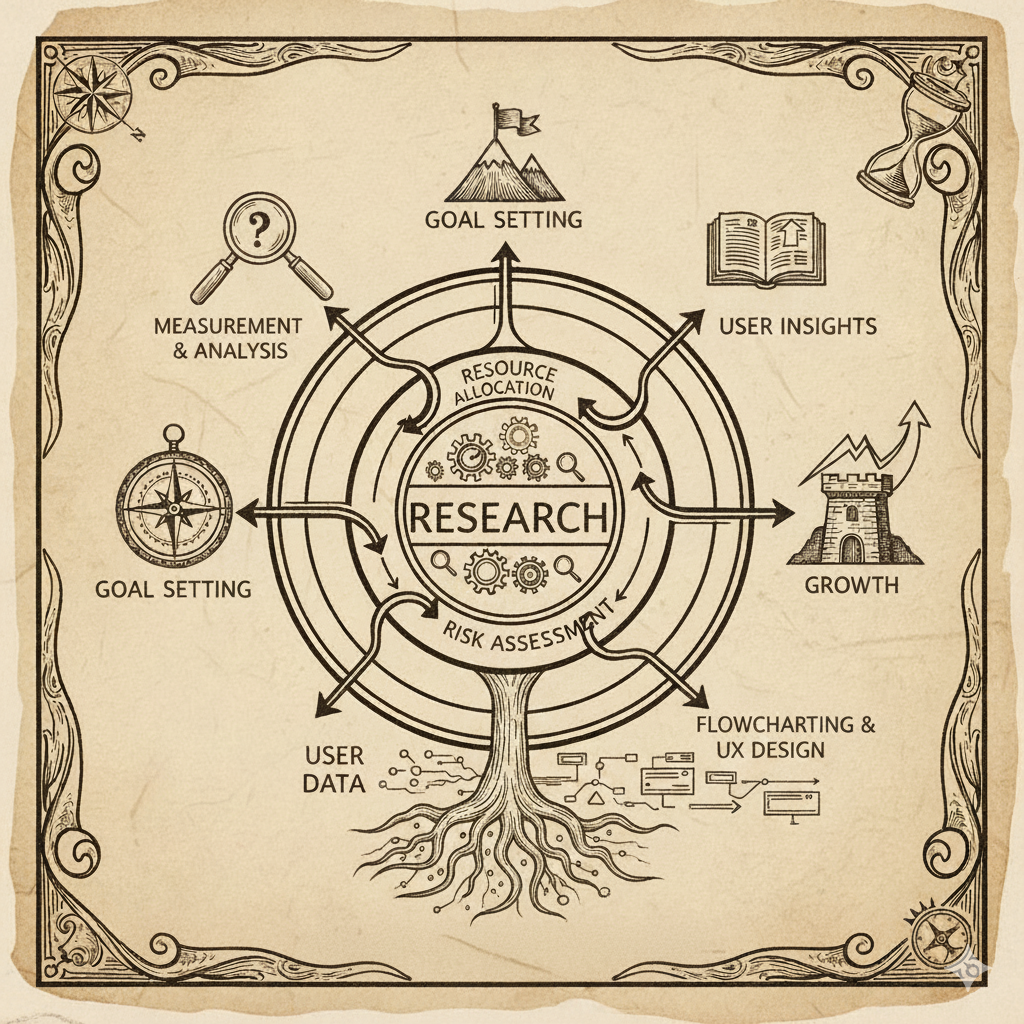

An overview of high level strategy, with concepts of operation for illustration.

First Principles: Why do we need user research?

Without constant buyer and user feedback how would companies dial in and course correct product? Researchers help answer the endless stream of questions around what to make and how to build. Great researchers translate learning to words and ideas anyone in a company grasps. Great researchers answer questions with data when decisions are made and not 3 weeks later. Great researchers can anticipate helpful inputs and work independently to answer questions not yet asked. When teams don’t have answers or don’t seek them out, they fly blind.

Scope: where we play.

We answer questions involving pharma customer users and buyers on behalf of anyone on a product development team (CFT) or senior leadership, with primary accountability to product management. We deliver first insights to most questions within a day and build confidence over 1-2 weeks.

Okay, break down why that matters?

Speed is key: History tells us that many successful companies first succeed because they are able to experiment, build, and refine more efficiently (and test more ideas) than competitors. Companies rarely get the right answer the first time.

Keep customers and buyers close. Know the difference: Successful teams frequently and opportunistically reach out to customers and develop proxies (e.g. academic scientists) to speed up work. Anyone, Product Managers, Designers, Engineers, could participate in research: Attending calls, putting ideas to customers or proxies, independently learning. No priesthood sits between the team and customers acting as a sole source of contact and interpretation. We believe teams work best, align well, and stay focused when each member hears directly from customers.

Be cash aware, but not miserly: BenchSci is not yet cash flow positive, nor is it entrenched. We run on a time clock. We earn seconds on days where deals sign, funding arrives. Market challenges cost us seconds. Because this clock never stops, we always need to consider the opportunity cost of our operational decisions. Have all the people you need and no more. Find a good compromise between speed and precision. If in doubt, go cheap and fast.

So how do we enable agile-speed answers …with Pharma?

What does the customer landscape look like? Pharma scientists as a group are very distinct from consumer software targets like tax prep:

- Not easy to recruit thru un-moderated testing pools (we tried)

- Show data they know in prototypes. Scientists respond very differently to data they know or techniques they work with frequently.

- Expensive to recruit outside of customers. Engaging a research recruiting agency costs ~$1000 per hour, with a 2-4 week recruiting time, and limited ability to record

- Favors, no comp. Customer scientists cannot be paid in any way for feedback – they volunteer out of good will or self-interest

- Busy Scientists are busy, well paid, professionals: there are many calls on their time and many companies looking to sell or collect feedback. Setting up calls can take a week or two at best with scientists we have an established relationship with.

- Secrecy: Drugs take a long time to reach the market, with significant first to market advantage. Research takes a while but is easy to ‘steal.’ So Pharmas build walls of access and protect their data.

- Difficult access: Onsite visits, particularly to facilities with manufacturing and research often require pre clearance and elaborate preparation, with limited ability to explore. Labs are often off limits, both due to secrecy and the polarizing nature of experiments which may use live animals.

Other qualities of our offering affect research:

- Low organic usage per user (1-2 active monthly sessions for engaged users. A typical session may span many looker sessions)

- Low total numbers of very high value users- ‘lead scientists’ are equivalent to engineering or product directors in a company like ours. When we are successful we may have thousands of users: a company like Facebook has billions. That changes how we can learn.

- Flows are exploratory, not linear or narrative. Unlike shopping checkout, business forms, or other linear flows, scientists use us more as a non-linear workspace. This makes it harder to learn with high polish, mostly linear, limited interactivity, slide-like prototypes of the kind made by Figma.

How does the landscape shape our response? (our strategy for excelling in this environment)

Solving for: low numbers of high value, difficult to access, unpaid customer participants.

- Pre-recruited proxy users – fast access, allows us to answer select questions with good correlation to ideal participants. Informally we call our set of industry scientists and academics our “academic pool,” and we compensate so we get reliable participation.

- Make the most of time: focus on techniques which extract the richest data per session and make participants feel value so they come back(ex. fewer but high quality moderated sessions which make use of many sub techniques as opposed to many surveys with low response)

- No touch deep observation (aka FullStory, Looker).

- Rely on available artifacts. We might not go to a lab, but we can see what story the slides, figures, sheets, and other artifacts tell about a process. For example, governance reports shed great insight into how customers value and contextualize different scientific information.

Solving for: Infrequent usage

- Separate training from real sessions – cross software data correlation (SFDC training dates, users, looker data.)

- Extend use to academia to scale user numbers – i.e. we get more users we can learn from

- Automated question capture – we capture when someone puts a question to XXX, inputs a structured query to YYY or ZZZ, or any future input in a yet to be developed product. We then passively track their response to our output.

- See every session – ex. fullStory segmenting

Solving for: Scientists respond differently to data they know

- Ensure scientific accuracy of research materials (low fidelity, high fidelity, engineered prototypes, cards for sort etc…)

- Where possible, match the materials to the participants background – e.x. Show publication examples relevant to the scientist’s specialty

- In prototypes, favor data accuracy and interaction over visual fidelity. I.e. A spreadsheet or informal engineering prototype may be richer for us than a refined figma. Vibe coding tools such as vercel can help in specific cases.

Solving for: Keeping up with engineering speed (agile)

- Decentralized / High Autonomy — Dedicate a researcher to each team that matters. Give them full authority to do the work. Emphasize fast, informal, flexible working where insight for a question happens in a day not weeks. Emphasize direct PM/Engineering contact with users to pre-build empathy. These are hallmarks of a research operations concept called continuous discovery/validation.

- Keep cost per insight or session as low as possible- Lower cost means more sessions

- Focus team core on enabling, coaching, and unblocking. For example: securing budget and executive buy-in, coordination of initiatives with go-to-market(GTM), coaching and teaching.

- Reduce long lead/ tail items on research through automation or process reduction. E.x. recruiting and de-emphasized write-up.